Escape Pod 1023: Mackson’s Mardi Gras Moon Race

Mackson’s Mardi Gras Moon Race

by David DeGraff

Turtles were built for short-haul Lunar prospecting, not treks across the entire face of the Moon, but back in 2043 João Silva Henrique, desperate to celebrate Carnaval, drove a turtle from Amundsen Crater at the south pole to Byrd Crater at the north pole. Unsanctioned celebrations of any kind were forbidden in the Chinese stations, but there were enough Brazilian workers at the north pole to make the risk of trekking across unexplored terrain seem worthwhile. Now that Brazil controls Byrd Station, it’s an annual race. And I’m going to win it. If I live.

We only have the equipment João used on his desperate first run when he stole his turtle—no moon suits, no long-range radios other than emergency receivers that only work when a rare comms satellite is overhead. Rescue could be too late, like it was in the ’52 race.

The hangar lights flash the race’s start. I kiss my fingers then touch the picture of Bernardino on the dashboard, the one from last year’s Carnaval, before slowly pressing my foot on the accelerator, hanging back as fifty racers flow from the airlock and stay in a tight peloton along the road to Amundsen Crater’s wall, the sun low on the horizon, shining on less than half our power films.

I don’t start at the front with all the elite racers, children of the founders of the Lunar Corporations with someone to sponsor them. They get to spend weeks training on un-tracked regolith, fine-tuning waste and oxygen recyclers, refreshing the solar-voltaic film over the cockpit bubble. They talk about needing to get used to the claustrophobia. Me, I’m used to it. This bubble is bigger than the room I share with Bernardino in the miners’ dome.

I want to be at the back so no one follows me. Trekking alone across unexplored terrain is the only hope I have to win against my better-funded competitors. It also increases my chance of dying. Half the people who try new routes need rescue. Some even have rescue reach them in time. None has placed in the top half of finish times.

Race radio squawks when the last straggler is at the top. “All clear. See you in ten thousand kilometers. Godspeed.”

Rooster tails of regolith kick up around me, people gunning motors to get ahead of the pack, but I keep a steady speed. Being in front this early isn’t an advantage. I’m heading farther west to my secret approach to the north pole, one I found on an old orbital photo.

Untrekked routes are risky, but I’ve spent a lot of time on the surface, racing to get my ice haul to the station so I can head back for more.

Colorful dots move across the crater floor below me as I ride along the next crater’s rim while the others take the well-worn route down its slumped wall.

The line-of-sight radio cracks to life. “Who’s on the ridge?” That’s DaCruz, who won three of the last five races, son of the founder of Fazenda Greenhouses.

I stay silent.

“Dull red turtle that hasn’t seen a paint job in five years? Mackson Coelho.” That’s Lopes, scion of the Paulo Mining Group. When DaCruz doesn’t win, Lopes does. “He came in thirty-third last year.”

Hey, I finished ahead of four people in a year with no fatalities, and my navigation skills got me a twenty percent raise when I left Paulo Mining. That counted as a win for me.

“What’s he playing at?” That’s Zezé Almeida, the top woman racer, who swears she’s going to win this year.

The peloton drops out of sight, out of contact, as I turn onto the altiplano heading to the 45° meridian. The half-illuminated third-quarter Earth hangs over the horizon. It’s early evening in Japan—no, that’s New Zealand. Earth is upside down from the way I usually see it.

I’m taking a path no one has tried before, a path that doesn’t look like it could work, but what I’m doing is closer to João’s spirit than any other racer in the last ten years. I can’t afford to push my batteries to the point where they’re useless by the time I reach the finish line. I’ll still need to use my turtle to mine the ice in the permanent shadows at the north pole.

I loosen my grip on the steering wheel and wiggle my fingers to get the blood circulating. It’s exhausting work looking for the shortest routes around the small craters, trying not to think about any cracks in the cockpit seals, not to think about failing oxygen recyclers or a crack in the still that treats my waste, not to think of all the ways to die out here.

The loneliness of this route is an added factor I hadn’t considered. There’s no chatter on the radio to keep my mind from wandering too far. I keep remembering the turtles of those who’ve died over the years—turtles wheels-up at the bottom of a crater, tracks disappearing into a dark hole on the slope of a rille, bubbles popped open rather than facing the slow, painful death of CO2 poisoning—left as monument to the harsh Lunar landscape.

The timer dings. Ten hours. I cut the power to the wheels and roll another thirty meters before I stop.

It’s tempting to eat the feijoada MRE but that’s a special meal for my last sleep, or maybe when it’s clear I’ll actually win. For now, it’s either pão de queijo or generic protein bars for when I don’t want to spend as much time eating.

When I sleep, I dream of a smooth road over the Lunar surface, paved in green glass.

When I wake, I check the latest race positions. I’m in second-to-last place. Everyone else is strung along the traditional well-traversed route. Names I don’t recognize are far ahead. They’ll eventually make a mistake in their exhausted state, or they’ll be passed when they oversleep. Or they’ll die.

Wait. Not everyone is taking the standard route—there’s someone five kilometers behind me, just over the horizon—Lopes. He should be in the peloton with DaCruz, Almeida, and the others.

The regolith is packed hard here, not churned over like it is near home. I adjust a degree east of my best heading, hoping to throw him off my true destination.

After my next sleep, Lopes is still four-point-eight kilometers behind me, just over the horizon. Now I wish I had something to obscure my tracks.

I use the turtle grapple arm to draw a rabbit and a wolf in the regolith, and write, “You can’t catch me.” It looks nothing like writing in the wet sand in Rio—the regolith compacts without raised ridges along the edge of the grooves. I trace a line dodging the tiny crater in front of the rabbit.

Hour after hour, day after day, Lopes dogs me, even matching my sleep cycle. The Earth creeps higher in the sky as the crescent wanes, and he’s still five kilometers behind, still just over my horizon. I try not to let it bother me, try not to let the uneasiness in my stomach keep me from driving my top speed, try not to look at the race updates, try not to worry he’ll win.

I have to navigate around a small rille. It might be a ten-kilometer diversion instead of a hundred meters across, but I don’t trust the slopes. That’s how Huang died in ’63. Rilles mean lava tubes and open pits, ground that could collapse under a turtle’s weight. The north end of the rille terminates in circular shadow—a cave entrance.

My next rest stop is southwest of Kepler, the sun directly overhead. I lie down, cover the sun with my hand, and search for the new Earth, its nightside facing us. I can see the white lights of Florida and Brazil. Rio shines.

Green flashes in streaks from the Antarctic Peninsula up the length of Chile. Another flash. Soon, half the Earth is bathed in shimmering red and green. Even the lights of Porto Alegre are covered. Aurora. A solar storm hitting Earth.

And me. If I can see the solar storm attacking Earth’s atmosphere, those high-energy protons and electrons are raining down on me, too, ionizing the atoms in my body, ripping me apart on a molecular level. Radiation is an ugly way to die.

I pull up the mic in case anyone is in range. “Warning. Warning. Auroral activity on Earth. Find shade!”

Training kicks in. Head to a shadow, a cliff base where you block the sun and thirty degrees to its right. But we are all in the mare, the smoothest plains on the Moon. Where can I hide? Where can anyone hide?

The lava tube. What is that, two, three kilometers behind me?

I gun the turtle and spin a sharp one-eighty, using all the solar power and battery reserve to follow my tracks south.

“Can anyone receive me?”

The electron storm blocks the radio signals. Lopes won’t hear me, even if he’s in range. Does he know how much danger he’s in?

Lopes is probably another three kilometers before the rille if he’s staying out of sight. Can I risk this much exposure? I don’t know, but I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t try.

“Lopes, can you read me?”

Silence.

I see him up ahead, no dust arcing behind his turtle. Stopped.

“Lopes!”

No response.

He’s sleeping in his recliner seat. I nudge my turtle forward and bump him.

He lurches, looks around, eyes wide when he sees me.

I point up, then reverse and spin, hoping he’ll follow.

This time I gun down the slope, sliding as the regolith shifts under my wheels. The ground slopes into a cave mouth barely wide enough for the turtle. I drive in ten meters. Where the lava tube ends, my headlamps shine on rocks no human has ever seen. Lopes’s beams shine through my cockpit, and I can see my shadow on the rough wall in front of me.

“Thanks, Mackson,” Lopes says over the radio. “You didn’t have to rescue me.”

I make a broad shrug.

“If the tables were turned . . .”

“You’d have done the same thing,” I lie.

“Sure,” he says after a long pause. Then, “You’re razing it, man. I don’t know how you can keep up this schedule. Four hours of sleep a day is brutal. I mean, we’re in the lead for now, but we always go the last forty-eight hours without rest, the people trying to win do. I don’t think you can do that.”

“You underestimate me, Lopes.”

“No. I looked up your last two races. You kept this same rigid schedule the whole time.”

I won’t play Lopes’s mind games. “Why are you following me, then?”

“You looked like someone with a secret. Like you scouted out a faster route, a route no one else would take. Your path through Lacus Excellentiae was a good find. You must have another excellent trick to get past the cliffs of Sinus Iridum.”

I’ve got him. He thinks I’m heading east of the Jura peninsula.

“Is that the game you’re playing?”

My body clenches despite my elation. “It’s not a game for me, the way it is for you rich assholes. I need the prize money. I need to leverage my navigation skills into higher wages.”

I grit my jaw when he laughs. If we were in a room together I’d punch his face. “I’ve spent quite a bit more money training than I’ll win. The race is supposed to be about honor, not financial gain.”

“That’s easy for you to say. Your family paid for your transport here. I might be able to pay off my fee before I die.”

I could feel a lecture coming about working harder, how the best people can rise above their birth, but three words into his rant, emergency tones scream through his radio, but not mine—I must be too deep to pick up the signal.

“What are they saying?” I ask.

“Everyone who can get to shade in ten minutes will be okay. Long-term effects will start to accumulate beyond that. Fatal in ninety minutes, and the storm will last another five hours. Time to catch up on sleep.” He clicks off his headlights.

Five hours. I set the alarm for four and hope the storm is shorter than predicted, hope no one tries to ride through it.

Why is it so dark? The storm. I’m in a lava tube with Lopes. But Lopes is gone. And a boulder blocks my escape. I should never have trusted that son of a mother.

My front grapple would get the boulder out of the way, but the tube isn’t wide enough to turn around, so I nudge it with my rear bumper and spike the motor in reverse. The rock moves a couple of centimeters. I spike the motor again and the boulder begins to slide. One more push and it slides farther, but the battery’s temperature rises into the danger zone. It will cool off quicker in the cave’s cold darkness than in the bright sunlight, but still slower than with an atmosphere. I waste a half-hour waiting for the motor to cool.

That monkey comber forced me to lose another hour pushing the rock far enough to escape, and I’m down to thirty percent power. I’ll need to move a little slower than I’d like so I’ll be fully charged when I reach my secret. If I run out of power there, will anyone ever find me? Would they even bother looking for someone like me?

Lopes left a message in his tracks. I can see where he harvested the big boulder and pushed it into place (much easier going forward and downhill), but he also moved four smaller rocks like he thought about wedging them in, locking the boulder in the lava tube’s mouth. One plume from a hopper and all trace of me would be gone, my body never to be found. So noble of him.

I want to take off, follow his tracks, and smash his bubble with my grapple. No. My best revenge will be to win the race, although that won’t be as sweet as plucking his body from the turtle and sweeping the regolith with his face. I’m here to win.

Earth is all city lights with no green flashes. Lopes lied about the storm’s duration. Why did I ever believe him? Never again.

A thousand kilometers to go if we had a hopper. Five days navigating across the surface in a turtle. Well, it would be five days if I had to worm my way around all the craters and debris. I can travel my path in four days. I won’t just win by a little, I’ll beat everyone by eighteen hours if I’ve done the calculations right.

Lopes is heading to Sinus Iridum where the Jura mountains will trap him. He won’t pay any more attention to me, so I turn a little west to go on the other side of the peninsula and reach Sinus Roris, where I do have a trick to make it through the mountains.

The cliffs of Sinus Roris are notoriously tall and rugged. I see their bright peaks pop over the horizon, brighter than the mare’s dark regolith, and stop when I can see the cliff’s base. It’s time for my last sleep before I find the tunnel entrance and take the fast lane to Byrd Crater and victory. I sneak a look at the positions as I eat my pão de queijo. Will I still win?

I’m even with Zezé, ahead of the main peloton which has pulled ahead of DaCruz. I hope he’s okay.

Lopes has switched course, heading toward me, but there’s no way he can catch up now. He might think he can, but while he skirts around boulders and craters, I’ll be making solid time. I sleep restlessly, but I feel good after a heavily caffeinated protein bar. My next meal will be my celebratory feijoada.

Craters deeper than my turtle are everywhere as I approach the bay, but not as bad as the highlands. As I round one final crater, I come to the base of sheer cliffs on the banks of Roris.

I don’t see my path—nothing but sheer cliffs. The old photo I found had the sun overhead, not leaving shadows pointed west. If I have to waste time looking for a small cave, I’ll be lost.

There’s a hill to let me see a little farther, so I run up it. There! Tracks, at least twenty years old if this was really an American project. There’s no record of this construction anywhere and no reason for this tunnel to exist.

Why did they build such a thing and abandon it? Were they planning a base away from the pole, away from the easy access to ice? A rail gun to send their ice to orbit? A weapon for revenge against the Chinese after they desecrated the Apollo landing sites? I don’t know, but the road is long and smooth and straight. They leveled hills, filled in craters, and dug tunnels. It will be easier than driving the rodovias, my speed limited only by how quickly the battery can shed heat.

As I approach the circular mouth, I see tire tracks, narrower than standard—Americans with their strange units of thumbs and feet instead of meters.

Ah, the tracks lead to small exhaust craters. This was a hopper launch zone, but with no infrastructure so it could remain hidden.

DaCruz still hasn’t moved.

I really hope this is a tunnel and not just a deep mine. But when I extrapolated a straight line from here to the highlands, I saw a hint of another cave with a narrow track heading toward it. I told Bernardino that I’d found a tunnel, but I didn’t tell him I was only eighty percent sure that’s what it was. If I’m going to die, this is where it will be. But I won’t die. I’m going to win.

The tunnel angles up, and my head lamps shine on the smooth floor unmarked by tire tracks or any trace of who dug this tunnel or why. I would have expected Americans to leave much trash behind, many useful resources, but the whole area is empty.

Before the race, I calculated how fast I can go balancing speed, distance, engine temperature, but I don’t know how much my batteries’ capacity deteriorated in the lava tube when they started to overheat.

The tunnel is straight and smooth, and I don’t need to think about the best path around craters and boulders. The turtle says power use is low, but still in the range I calculated. I’d given myself a twenty-five percent margin of error, so I kick my speed up a little.

After two hours, the line-of-sight radio cracks. Lopes has gained on me faster than I expected him to. “I see you up there, you little rabbit. You still won’t win this race.”

I reach for the mic but stop. I won’t rise to his bait again.

He mercifully stays quiet. For a little while.

“I’m gaining on you, Coelho.”

Or he’s increasing his head-lamp brightness to fool me. I push on, ignoring his taunts.

After an hour I can see a tiny light ahead—the end of the tunnel. If it weren’t for Lopes, I’d be able to compare both ends, judge my remaining time better, but I think I’ve got five hours to go, and my batteries are above fifty percent. I push faster.

My mind stays engaged when I’m navigating the surface—always scanning ahead for the smoothest routes. Here the floor and the curved walls merge around me forming a tube, smooth and monotonous, but I have to steer straight, so I can’t let my mind wander too far, can’t let myself imagine the victory, imagine Bernardino’s embrace when I finally return to him. If I scrape the side of the tunnel at this speed my canopy could crack and I’ll be dead.

My battery drops below thirty percent. If I run into a boulder or a pit and can’t move forward, I won’t be able to make it to the tunnel’s end, and I’ll die here.

Slowly the light grows, and it clearly has the same shape as the walls around me. It is truly a path out. I only need to worry about a cave-in beneath the floor.

“What the hell is that?”

I resist the urge to slow.

“Did you see the cave, Coelho? The walls look like quality ore, but the Americans found a mother lode and refined it in secret.”

Lopes can swallow frogs. The Americans wouldn’t have abandoned the Moon if they had all that. But the walls do look mineral rich. I drive faster so the batteries will be pushing empty by the time I emerge in the sunshine. His lights fade as I pull ahead.

How dumb does he think I am?

“Don’t tell anyone about what we found,” Lopes says. “I’ll hire you at five times what you’re making now to help us extract this material.”

I shut off the radio for four more hours until I’m back in the sunshine. There are signs of another hopper landing zone, but there’s no equipment on this side, either. I see tracks where they must have carted off the tailings from the tunnel to make the road less conspicuous, but no abandoned hardware.

The road leading away is narrow—too narrow to be noticed on orbital maps—but it’s packed tight and smooth. Not as smooth as green glass, but I won’t leave tracks for Lopes to follow. I only have a two-hour lead. I can’t take time to sleep for the rest of the race. I should have eaten the feijoada yesterday. The batteries aren’t charging as fast as they should. Did my panels get covered in dust, or are my batteries failing?

I set the display to update every ninety minutes to make sure I stay ahead of Lopes. I’m going to beat the lead group by almost a day.

The road skirts around a few hundred-meter-wide craters, and it switchbacks into and out of Pascal Crater, but it still drastically cuts the total distance.

The next update, Lopes’s gaining on me, and soon I can see his lights.

I’m not so sure of myself now. I’m burning more power than the sun can give me, and my batteries are draining faster than I expected. I’ll cross the line twenty-seven hours before Zezé and the rest of the main pack, but what if I’m in second place? Second-place purse won’t cover the cost of a new battery pack.

I push the motors as hard as I can, but my speed starts to drop. Is my lead good enough?

In an hour the beacon light flashes on—I’m in radio range. “This is Mackson Coelho approaching finish line.”

“A full day ahead of the previous record, Mackson. If you can stay ahead of Lopes.”

I can see the hanger. I can see the yellow ribbon strung across the opening. I can see a tail of regolith flying behind Lopes’s turtle, and it’s getting bigger.

I push harder on the accelerator, but no speed comes. He rips past me and dust crackles on my roof. He breaks the yellow ribbon and passes the rainbow-leafed palm trees and colorful parrots. People inside the second-story observation deck raise their hands and jump. Bernardino is there, looking down, his forehead resting on the glass.

I pull past bikini-clad mannequins whose silver masks and sparkling bodies mock my loss. I’ve lost the race. I’ve lost my turtle. I’ll probably lose Bernardino, too. I gambled everything and lost.

The airlock hisses at me, but I don’t pop the turtle’s seal until I see Bernardino. He wraps me in a tight, loving embrace. “You’re alive, Mackson. You’re alive.” He steps away and waves his hand in front of his nose. “But first you need a shower.”

I nod and turn to go, but my eye catches the wall next to the window overlooking the docking bay showing all the positions. One red dot sits in the center of Imbrium Basin. DaCruz hasn’t moved in three days.

“He thought the storm would blow over before it became lethal,” Bernardino says. “The rescue jumper said he popped his hatch rather than deal with all the organ failure. Another monument.”

I hope DaCruz turned south to face Earth for all eternity.

A short man with a fringe of gray hair approaches me, hand extended—Lucas Saures, top boss of Peripo Mining. “Congratulations, Mr. Coelho.”

Technically, he’s my boss, but so far up I’ve never seen him in person. I shake his hand and introduce him to my husband. “I don’t know if you noticed, but I wasn’t the guy who crossed the line first.”

He waves a hand dismissively. “When your signal disappeared, I looked over your route—your route, Mackson, yours. Once I knew it was there, I could see the tunnel and the road you took. That was surprisingly brilliant.”

I shrug.

“We could use someone like you in our company. In our offices, I mean. No more endless days cramped in that turtle. With your eye I bet you could help us become the largest mining operation on the Moon.”

Bernardino bounces a foot off the floor. “We need class-two living quarters.”

Saures laughs. “Class-four is still a step up from the miners’ dome. We might get you into class-three if you’re even better than I think. Your pay will depend on what you find, of course. And if you don’t bring it in fast enough, you’re back to the turtles.”

I hold out my hand. “Get hoppers to both ends of that tunnel. Quickly, before Lopes sees you talking to me.”

Saures looks me in the eyes for several seconds, nods and walks off.

Bernardino grabs me in another hug, then pushes me away. “Let’s get you in a shower, and then we can celebrate properly.”

I may not have won the race, but this is going to be the best Carnaval ever.

Host Commentary

And we’re back! Again, that was Mackson’s Mardi Gras Moon Race by David DeGraff, narrated by Brian Lieberman.

About this story, David DeGraff says:

My friend’s annual Mardi Gras party was one of my last group activities in 2020, and at the beginning of 2021 I realized she was going to have to cancel that year’s party. Then I thought of my Brazilian friends in grad school—whenever I went to their house, the Rio Carnival was always on the TV. So of course, my next thought was, “What would that look like on the moon?”

David also says: I’d also like to thank Sheree Renée Thomas for her suggestions to improve the ending, throwing some extra regolith in the works.

And about this story, I say:

I thoroughly enjoyed the solid, fun adventure feel to this story. DeGraff puts us solidly on the side of our underdog racer, trying to use brains, research, and calculated risks to do what the rich, comfortable racers might not. It was also great fun watching the double-crossing nepo baby racer get his just desserts at the end, when he loses out on the bigger prize of the new mining site.

I could definitely see this as a fun action-adventure movie–the exciting moon race full of underdog heroes and wealthy doublecrossing villains. Throw in a few flashbacks to Mackson’s physically demanding job in the mines, his previous run-ins with his wealthy nemesis, his relationship with his husband Bernardino–I mean, yeah, I’d watch it! Someone get on that.

Escape Pod is part of the Escape Artists Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and this episode is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Don’t change it. Don’t sell it. Please, go forth and share it.

How do you share it, you ask? Well! In addition to your social media of choice, consider rating and/or reviewing us on podcast listening sites, such as Apple or Google. More reviews makes for more discoverability makes for more Escape Pod for you.

Now if you’re a new listener this week then you may have missed our news this fall that we are going to be including brief ads that run at the beginning and end of episodes (but never ever in the middle.) (And if you have heard me say that before several times, then don’t worry, this is the last time I’ll say it for awhile.) If you wish to avoid those ads, get premium content, and support Escape Pod all in one fell swoop then just hop on over to escapepod.org or patreon.com/EAPodcasts and cast your vote for more stories that trek across the unexplored terrain.

Our opening and closing music is by daikaiju at daikaiju.org.

And our closing quotation this week is from Tex Dinoco, who famously said to Lightning McQueen: “There’s a whole lot more to racing than just winning.”

Thanks for listening! And have fun.

About the Author

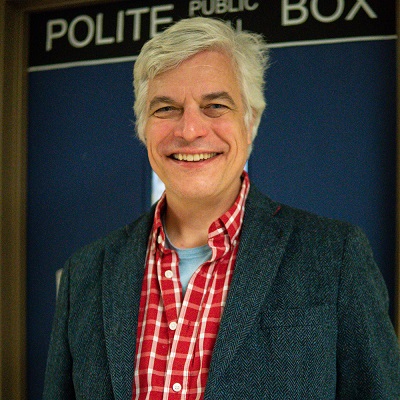

David DeGraff

David DeGraff taught physics and astronomy at Alfred University in Alfred NY. In addition to the usual physics and astronomy classes, he also taught classes on the Theory and Practice of Time Travel, the science in Star Trek, Doctor Who, Harry Potter, Superheroes, and Supervillains. His fiction has appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Lightspeed, and other places.

About the Narrator

Brian Lieberman

Brian Lieberman has been many things at the Escape Artists Foundation, first finding his footing back in 2007 as a moderator for the newly minted forums. These days, he’s a Solutions Engineer, helping to manage some of the back-end technologies that help keep the wheels spinning and the stories coming. When he’s not doing all of that, he’s fighting various evils with his friends or cuddling up with his wife and two corgis.